The Class That Never Was

This story was originally published in the Sandlapper, Autumn 2009. It is posted here in its entirety with the permission of the author.

The 1940 plebes prematurely were carried off by a small diversion known as “World War II.”

At mess one day in 1943, The Citadel Class of ’44 were ordered to stand up. They heard the words: “Gentlemen, you are shipping out.”

By Sheila Collins Ingle

“A place for everything, and everything in its place”—one of many Citadel standards. (Courtesy of Sheila Collins Ingle)

In 1940, World War II enveloped Europe. Belgium, Norway and France surrendered to the German Army. Italy, siding with Germany, declared war on Britain and France in June. Hitler’s parade into Paris was broadcast in American theaters on Fox Movie-tone News. Air battles and daylight raids between the Luftwafte and the Royal Air Force over Britain’s skies began in August. Men, women and children were dying.

That same year in America, Big Band sounds filled the air waves and dance floors. Crooner Bing Crosby and comedian Bob Hope made their first movie together. Everyone flocked to laugh at My Favorite Wife and The Philadelphia Story. (Our Office of War declared movies essential for morale and propaganda.) But in May, the country listened to President Franklin D. Roosevelt give a “Fireside Chat” on National Defense. He looked backward and forward at the situation in Europe and its future

effect on America.

World War II was winding closer to home shores.

On September 2, 1940, 565 high school graduates reported to The Citadel in Charleston for their freshmen year of college. They came from across the United States. Each enthe same wrought iron gate. Young men arrived from California, Indiana, Pennsylvania . . . but most were South Carolinians. Registration began at 9 a.m. in the armory with forms to fill out and fees to pay. Freshman expenses were $531.50 for first-year South Carolina cadets, $671.50 for out-of-state cadets. Gen. Charles Pelot Summerall, Citadel president, welcomed the class that night.

Among “the class that never was”—the anticipated Class of 1944—not one at the time could have imagined there would be no cadets in what would have been their graduating class.

That first week was packed with new experiences. Padgett-Thomas Barracks was their new home. Rooms were no larger than oversized closets of today. Each cadet had a spring cot. They kept their mattresses in a press and folded up the cots for daily inspection. The barracks were fully screened, but the screens didn’t keep out the mosquitoes and “no see-ums.” “Air-conditioning” was free. (No charges are listed for it among freshman expenses.) (There was a sink with cold and hot water in each room.)

Reveille, the bugle wake-up call, sounded at 6:45 a.m. the first week, at 6:15 the rest of the year. There would be no turning over for a few extra minutes of shut-eye. The training cadre was meticulous in introducing the new class to all facets of cadet life, and that included early rising.

Each cadet received a copy of the Guidon. This was the information guide to help a new cadet survive his rigorous first year. Cadets had to memorize the Guidon’s three most important questions and be ready, willing and able to recite them at any place, under any circumstance:

1) What is the definition of leather? “The fresh skin of an animal, cleaned and divested of all hair, fats and other extraneous matter; immersed in a dilute solution of tannic acid, a chemical combination ensues; the gelatinous tissue of the skin is converted into a nonputrescible substance, impervious to and insoluble in water; this, sir, is leather.”

What time is it? “Sir, I am deeply embarrassed and greatly humiliated that due to unforeseen circumstances over which I have no control, the inner workings and hidden mechanisms of my chronometer are in such in-accord with the great sidereal movement by which time is reckoned that I cannot with any degree of accuracy state the exact time, sir; but without fear of being very far off, I will state that it is [so many minutes, so many seconds and so many ticks after such an hour].”

What do freshmen rank? “The president’s cat, the commandant’s dog, the waiters in the messhall, and all the colonels at Clemson.”

“Ten-hut!” (“Attention!”) was quickly understood. Cadets prayed to hear, “As you were, Mister,” while standing at “ten-hut.”

Plebes (first-year students) had daily opportunities to become more adept at push-ups and pull-ups. “The Citadel takes boys and makes them men,” observes Bob Adden, a Class of ’44 member from Orangeburg. Lee Chandler of Greenville, retired S.C. Supreme Court justice, says he rapidly came to see “the value of living a life of discipline and control.” The first six weeks were hard, but he decided “to not be a quitter, even though not of a military inclination.”

Freshmen quickly learned to stand at attention and parade rest, to answer all questions with the prefatory and ending address of “sir,” to clean and carry a rifle, to walk square corners and eat square meals, and to march double time everywhere. Answering immediately to names like “Mr. Dumbsquat” and “Mr. Doowilly” became second nature. They became skilled at not blinking at gnat and mosquito attacks on the parade field.

Study hall, 7-11 p.m., was enforced by upperclassmen. Days started at 6:15 a.m. and ended with taps, the bugle signal for lights out, at 11 p.m. A duty officer then checked the occupancy of each room. Some cadets called The Military College of South Carolina by another name: “The Sing Sing on the Ashley.”

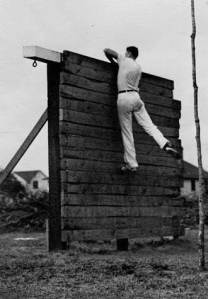

Sam Piper on the obstacle course in 1943, just before going to war. (Courtesy of Sheila Collins Ingle)

The Citadel prided itself on its military training and environment. Self-discipline controlled every hour of the day. It “was very good for me,” says Edward Haynesworth of Sumter. His father and two older brothers were Citadel graduates before him. Sam Collins of Shelbyville, Kentucky, says his older brother Wallace, two years ahead of him at The Citadel, helped keep him from making too many mistakes. Arthur Cummings of Greenville chose The Citadel because he knew others who attended and admired their character.

All plebes cringed at the order, “Drive by my room.” This command was issued by an upperclassman to a fourth classman (freshman) for more obedience training. Constant inspections by upperclassmen on the plebes’ uniforms, actions and room status kept them vigilant.

“Walking a tour” was to be avoided at all costs. “Tours” were walked on a weekend when a cadet was supposed to be at liberty. The one-hour walk carrying a rifle at shoulder arms around the quadrangle was monitored, and this “opportunity for marching” was meted out regularly. “You finally get used

to the regulations,” Sam Piper of Greenville says.

Plebes learned to discipline their actions, thoughts and words. Their camaraderie grew daily. They respected one another for persevering. “The camaraderie fed on itself,” Chandler recalls.

The Citadel ring was the ultimate prize. Like all those before and since, the fourth classmen of 1940 craved their graduation rings. But The Citadel’s training was and is to prepare soldiers to serve their country.

“It is believed that considerably more than half our living graduates, and a like proportion of our ex-cadets, are now in the service of the United States, with more entering every day. Each of these men symbolizes The Citadel’s essential teaching — service and sacrifice.”

– Gen. Summerall

On September 16, 1940, President Roosevelt signed the Selective Service Act—the first peacetime conscription bill. All men 18 and older were eligible for the draft. Now, the Class of ’44 had greater concerns than walking a tour. Training intensified.

Some fourth classmen enlisted by the middle of their first year. Sherrill Poulnot of Charleston waited until 1942 to join the Navy. (“Three meals a day and a dry place to sleep was not so bad,” he reflects.) Only 428 of the entering 1940 class returned for their sophomore year. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, prompted still more war volunteers from the class.

The Army Specialized Training Program was launched in December 1942; only a few specialized students would be allowed to stay in school. Changes were made in The Citadel’s calendar, faculty were informed of their new military status, and training in the rules and practices of war for Uncle Sam accelerated by the day.

Daily, recent Citadel men were reported as dead, missing in action or prisoners of war. In his foreword to the December edition of the Alumni News, Gen. Summerall wrote, “It is believed that considerably more than half our living graduates, and a like proportion of our ex-cadets, are now in the service of the United States, with more entering every day. Each of these men symbolizes The Citadel’s essential teaching—service and sacrifice.”

“The Enlisted Reserve Corps [ERC] told us we would get to graduate, just not when,” says class member Bob Adden.

At the end of their junior year, the Class of ’43 recommended to Summerall that the Class of ’44 receive their class rings early. The general approved. What was so important about The Citadel ring? “Everything!” says Sam Collins, the Kentucky classmate.

Related: I wear the ring

On May 2, 1943, the Class of ’44 marched to the Charleston station and boarded a train. They traveled to Ft. Jackson in Columbia to be inducted into the armed services. After processing, the train returned them to The Citadel. The United States had called the Class of ’44 to their duty—a duty for which The Citadel had trained them.

The cadets finished their junior year and received a two-week furlough, then were ordered to 13 weeks of basic training. Officers Candidate Schools were the next stop. Then they were commissioned.

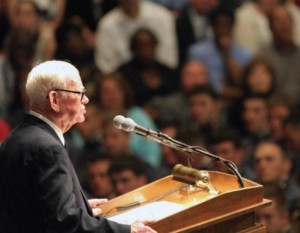

Retired state Supreme Court Justice Lee Chandler addressed Citadel graduates at an emotional ceremony in 2008. (Russ Pace/The Citadel)

For many, active duty ended in January 1946. Thirty-four soldiers from the Class of ’44 gave their lives to protect their country. Six were prisoners of war; four were imprisoned at the same time at a camp in Schubin, Poland. Countless received Purple Hearts, Silver Stars and Bronze Stars. They joined other Citadel men as guardians of freedom.

Some continued active service after the war was over. Some finished their education at other colleges and universities. Others returned to The Citadel to complete their senior year for graduation as veteran students; 152 from the Class of ’44 received diplomas from The Citadel in 1946 and 1947.

On Page 9 of the 1940 Guidon are Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s words: “The destiny of any nation depends on what its young men under twenty-five are thinking.” The “Class of ’44” were men of character, dependability and self-reliance.

In 1954, the class gathered for their first reunion at The Citadel, and they have met every five years since then. In 1994, they finally received their 1944 yearbooks. Many class members wrote synopses of their memories of The Citadel and the war years. The annual includes pictures from earlier annuals and statistics about the class.

In May 2008, 17 members of the Class of ’44 attended the 2008 Citadel graduation exercises. The Class of ’44 was recognized with speeches and given a standing ovation. Lee Chandler spoke for the Class: “The ‘Class That Never Was’ has become the class that always will be.”

The class celebrated its 65th reunion at The Citadel’s homecoming November 7, 2009.

Author’s Note:

The daughter of Sam Collins, I grew up attending many Citadel parades on homecoming reunion weekends. I watched the “Class of ’44” gather to stand in review. The corps marched past; cadets and graduates held their backs straight and tall. I remember the excitement of those alumni at seeing one another again, shaking hands and pounding backs. They huddled in tight groups, not wanting to miss one another’s words. Their grins of greeting were contagious.

After interviewing many of them for this article, I understand more about their closeness. They were all called to active duty at the same time and were trained by example. Retired Rev. Edward Haynesworth observed that Gen. Summerall “didn’t ask them to do anything that he didn’t do.”

All the cadets were required to attend chapel services on Sunday; the general attended, also. The general often wore a cape, and his exemplary military bearing made an impression. The corps would stand in front of his home to sing “Happy Birthday” to him before breakfast. Dressed in his uniform with all his medals, he greeted the cadets with, “Gentlemen, this is indeed a surprise!” Gen. Summerall’s example followed them overseas.

Many Citadel soldiers served in the same divisions during the war. Their training at The Citadel made them strong, and it didn’t break them.

I and my brothers, Critt Collins, Citadel Class of 1973, and Lee Collins, had the privilege of being reared by a Citadel Man, so we closely observed his character. He taught us the importance of always doing the right thing.

—Sheila Collins Ingle

About the author:

Sheila Collins Ingle, an adjunct instructor at USC Upstate in Spartanburg and a weaver of stories of America’s forgotten heroines, is the author of Courageous Kate, a Daughter of the American Revolution. Awarded the 2007 D.A.R. Historic Preservation Award, it is a biography of Kate Barry, a South Carolina Revolutionary War heroine. Ingle also has written a teacher’s guide CD to accompany the Kate Barry biography. Please visit her weblog at https://sheilaingle.com/

This is wonderful!!