He Served: Henry Garlington, ’45

Published in August, 2012, this article originally appeared in “The Skinnie“, Skidaway Island’s local magazine (Savannah, Georgia). It is posted here in its entirety with the permission of “The Skinnie”.

by Ron Lauretti

Henry Garlington’s story is amazing. it’s about a daredevil World War II fighter pilot, but it’s also the chronicle of a family tree full of fighting men, one who rode with General Custer (of Little Bighorn fame) and another who sailed with Commo. Perry (the commodore who opened Japan to the West).

In this story, Garlington is the aforementioned fighter pilot and a long-time Savannah resident. He moved to The Marshes of Skidaway Island several months ago. His memories include combat sorties and captivity, when he was imprisoned by the Germans after they shot him down over Italy.

But first, more on Garlington’s kin who preceded him in service to the United States…

Commo. Henry W. Fitch of the Navy was Garlington’s maternal grandfather and he sailed as an officer aboard one of the ships in Commo. Perry’s four vessel flotilla that steamed into Tokyo Bay on July 8, 1853. That expeditionary voyage was significant, as it prompted Japan to abandon its centuries-old isolationist policy, which opened up trade routes with America. Fitch was a career officer in the Navy who eventually rose to the position of Chief Engineer of the Navy and retired as a commodore.

Garlington’s paternal grandfather, Ernest Albert Garlington, graduated from West Point on June 15, 1876, and the newly commissioned second lieutenant promptly report for duty with Custer’s 7th Cavalry Regiment, headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas. A long trip by train and stagecoach deposited the young officer of regiment headquarters three days after many of the men had left for Little Bighorn and the subsequent slaughter there. However, in years to come, he saw considerable action in other military engagements. At the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890, the elder Garlington was seriously wounded and awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery. He fought in the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine American War (1891). In 1883, he commanded a bold, but unsuccessful relief expedition to rescue the Greely scientific mission, which consisted of a group of 26 volunteers who sailed into the frozen Arctic and were stranded in the icy wasteland for three years (only six survived). Eventually, Garlington progressed to the rank of brigadier general and retire from the Army in 1917. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Gen. E.A. Garlington had a son, who was Creswell Garlington and would become Henry Garlington’s father. Creswell, like his father, was a graduate of West Point and a career Army officer in the Corps of Engineers. He served in both World Wars. In the first, while serving with the with the 77th Infantry Division near Merval, France, a Lt. Col. at the time, Garlington was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart for an offensive assault on September 14, 1918, against heavy German fortifications. During the second World War, he served as the War Department Liaison Officer with the Navy and later as the commanding general of Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, which was the training center for replacement engineers. Early in his career, Garlington helped build fortifications to protect the construction of the Panama Canal. The general retired in 1945, after suffering a stroke and is also interred at Arlington.

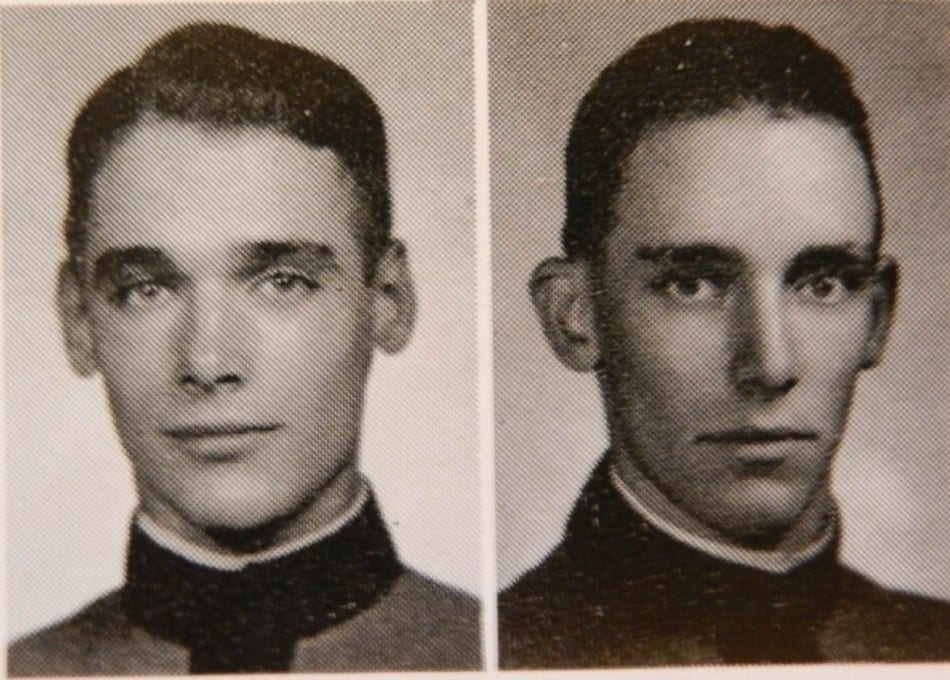

Creswell Garlington and his wife Alex had three children, twin sons Henry and Creswell, Jr., and daughter Sally. Both twins went on to distinguish themselves during World War II. They studied at The Citadel in Charleston and left early to attend to active duty because of the manpower requirements of the raging war. Henry joined the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet while Creswell, Jr. entered the Army’s infantry.

Creswell Garlington, Jr., Class of 1944, and Henry Fitch Garlington, Class of 1945. After completing three semesters, Henry left The Citadel December 1942 to volunteer for the Air Corps. Creswell, along with the entire Class of 1944, departed The Citadel at the end of the Spring semester, May 1943, and entered the Army’s basic training. Photo source: 1942 Sphinx. /RL

Henry progressed to single-engine flight training; he would be flying fighters. He earned his wings and his commission after completing advanced flight school at Dothan, Alabama in the fall of 1943. He laughs when he says most aviation cadets were hoping to become hotshot fighter pilots because the young ladies seemed to like this bold breed of aviator and the small cockpit seemed less vulnerable than a big-body bomber. It turns out that girls did like fighter jocks, but the small combat planes offered no guarantee of safety.

The young lieutenant was assigned to a P-40 fighter (the plane of Flying Tiger fame) training squadron where he simulated combat flying at Pinellas Air Force Base in St. Petersburg, Florida. He shipped off to North Africa in early 1944. Garlington flew a British Spitfire but saw little combat over the African desert, as the last units of the German Afrika Korps were bugging out and heading to Italy. Garlington was transferred to the 324th P-40 Fighter Group, stationed in southern Italy near Naples. He was then assigned to one of the 16-plane squadrons, the 314th, known as the “Hawks,” and flew 40 combat missions against German ground forces retreating up the boot of Italy. On June 5, 1944, only one day after Rome fell to German occupation, and a day before the Allied invasion at Normandy, Garlington’s luck ran out.

The P-40 Warhawk was a singleseat, single-engine, low-altitude dive-bomber with three .50-caliber machine guns on each wing. It could carry a bomb payload up to 2,000 pounds. It could fly fast and high but had a relatively slow climb rate, hindering the plane in a dogfight. The Warhawk was deadly against enemy positions on the ground. On June 5, Garlington was making such a run.

He was cruising north of Rome in his P-40, named “Betty,” searching for German ground targets. He quickly found one, a German truck convoy heading north. Bringing Betty down to treetop level, Garlington began strafing the line of vehicles along the road. He landed a series of direct hits but suddenly lost power in his engine. Evidently, the convoy hit the plane with rounds of return fire. Unable to climb high enough to bail out, Garlington was forced to make a belly landing in the field next to the truck convoy. Shook up but with no broken bones, he cautiously climbed from his wrecked aircraft. Somehow, he found the strength to run for cover, inspired by incoming German bullets, no doubt.

The going was very slow in the field covered with thick bramble bushes and his German pursuers quickly caught him. Garlington learned that the retreating truck convoy was a support element for Hermann Goering’s crack Panzer Division, not noted for its kindness to prisoners. His captors quickly took Garlington to a nearby tree and threatened to hang him. Fortunately, a German officer rushed to the scene and stopped the intended atrocity. He felt that a live POW as a potential source of information was more valuable than a corpse. So, Garlington was taken to an advance German field headquarters. He says that the lynching threat was the scariest part of his internment and he jokes that his misadventure on June 5 was dwarfed by immense historical events like the aforementioned D-Day.

Garlington was placed with other POWs and taken by truck through northern Italy for a two-week detention in a primitive dungeon in Florence. He vividly remembers two things – the beginning of neverending hunger pangs during his captivity and the surprising amount of information the Germans already had about him by tracing his dog tag number. Because Garlington’s father was a general, the Nazis had a rather complete dossier on the family, even though Henry had divulged nothing but name, rank and serial number.

Soon, the young aviator was transferred to Stalag Luft III, which was about 90 miles east of Berlin. A few months before Garlington arrived, the prison was the site of the Great Escape, when a total of 76 prisoners escaped through a long tunnel into the surrounding forest. Of the 76, only three made it back to England. Twenty-three were recaptured and returned to the camp, while 50 were murdered by the Nazis on direct orders from Hitler.

Garlington would remain a POW for 10 more months until liberation by American forces on April 29, 1945. His internment was a familiar story – crowded barracks, boredom, little or no contact with the outside world, and not enough food. The food was not only scarce, but it was lousy. Mostly some sort of foul potato soup and sawdust-laced bread. “Thank God for the Red Cross food packages,” he says.

The last weeks of captivity were the worst for Garlington and his mates. They could hear loud artillery barrages from the closing Russians on the eastern front. They were ordered by the guards to leave camp and began a long and punishing trek westward, first by foot, and then by cattle car. Men died along the way from malnutrition and illness. During the journey, the train stopped next to the Dachau concentration camp. From the limited view of their cattle cars, the POWs could see the wretched condition of the desperate survivors lined up inside the perimeter fences. Leaving the proximity of the notorious death camp, the POWs reached the putrid Moosburg camp, 25 miles northeast of Munich. It was terribly overcrowded; originally built to hold 10,000, yet packed with more than 100,000 Allied prisoners.

The war was nearly over. The guards knew it and laid down their arms before the tanks of the American 14th Armored Division came crashing through the main gate.

Several weeks later, after medical treatment, Garlington arrived at the French port of Le Havre for transportation home. In Le Havre, Garlington received some crushing news from a cousin who was able to locate him. His twin Creswell, Jr. had died December 3, 1944 from wounds suffered while fighting against the Germans and Creswell, Sr., their father, had died in Savannah on March 11, 1945, after suffering a severe stroke. As Henry boarded the homeward-bound troop ship, his joy of liberation gave way to a heavy heart.

Creswell, Jr., subsequent to his death, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart. He had graduated first in his officer training class and was assigned to the 84th Division. He had been in The Netherlands with the 335th Infantry Regiment, Company I, as a platoon leader. While his platoon was heavily involved in action late in November, 1944, he had demonstrated relentless bravery by engaging enemy machine gun emplacements, breaking up infiltrating enemy patrols, assisting in the elimination of a large number of enemy soldiers and carrying a wounded member of his platoon through intense hostile fire to safety. As the battle raged, an artillery shell landed near him and he was severely wounded. At an aid station, he insisted other wounded soldiers be treated first. He died two days later while receiving a blood transfusion. He is interred in a large American military cemetery in The Netherlands, and his twin brother Henry has visited the sacred gravesite to pay his respects.

Henry Garlington’s voyage from Le Havre to New York Harbor was hardly a pleasure cruise. Conditions were very cramped and the chow lines were long and slow. Still, he exclaimed, “So what?! We were on our way back home!”

Garlington returned to Savannah, where his recently widowed mother was living. After some well-deserved leave time and an accumulation of back pay, he returned to duty in the Army Air Corps with an upgrade from Reserve to Regular officer status. Things were to his liking for a while, until he was removed from flight status and made an investigator. That was a little too slow for the hotshot-at-heart, so in 1955 after 15 years in uniform, the captain resigned from active service.

After several interim jobs, Garlington found his permanent civilian calling in the field of finance. He became a trust officer for the former Savannah Bank and Trust Company and remained there until his retirement in 1984.

Soon after returning to Savannah from the war, Garlington met an attractive young lady named Jeanne Morrell. The two were married in 1949 and remained wedded until her death in 2003. They had two daughters, Katherine and Nina, and there are two grandchildren in the family.

Commo. Fitch, Gens. Ernest and Creswell Garlington, and twins Creswell, Jr., and Henry Garlington all served with distinction and valor in the ongoing fight for liberty. Two are buried in Arlington. One died in combat. One was captured by the Nazis after his plane was shot down. This family has answered its country’s call time and again. We are grateful to all of them.

About the Author:

Ron Lauretti – a Marine who served in the Korean War and who now writes about veterans for the Skidaway Island-based magazine, “The Skinnie.”

What a great and goosebump inspiring history. It gives further insight into the ³greatest generation² and what they endured, something that our generation mostly has no knowledge of and our kids¹ generation has not a clue about, nor do I wish they ever learn these lessons the hard way.

Thanks for sending out these missives that keep our perspective sharper.

Cheers,

Rick Ball

On 7/28/14 3:05 PM, “The Citadel Memorial Europe”

Hi and blessed greetings

My name is

De’Borah A Garlington born in the United States

to Frederick Carl Garlington would like to know about more about the ancestry of where I come from. Sunstar60.freeme@gmail.com

Is he still around ? I had a relative who may have trained and flew with him at Pinellas and in Italy/Corsica. I’ll leave my e-mail address

Hello, Mr. Martanovic. Thank you for the contact. I have forwarded your note to his family.