Citadel Men and Margraten Boys

Among the 8,301 American G.I.s interred in the Netherlands American Cemetery at Margraten there are eight Citadel Men. All eight died fighting Nazi Germany. Some died in the Province of Limburg just north of where they are now buried. Some died not far over the border in Germany, and another died deep inside Germany just weeks before the end of the war. They made the ultimate sacrifice for their country, and now they rest in peace in the country they helped to liberate.

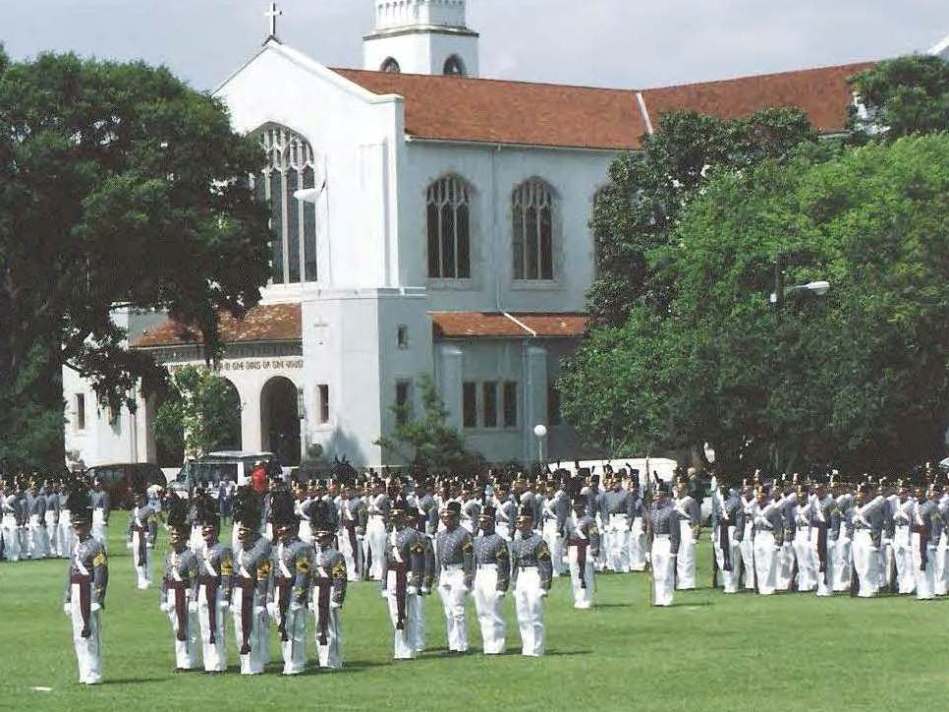

Dress Parade of the South Carolina Corps of Cadets on The Citadel campus, Charleston, S.C.

I had always been interested in WWII, and when I arrived as an 18 year old on The Citadel campus in August 1985 there were many reminders of the war such as a Sherman tank and the H.M.S. Seraph monument. What interested me most though were the bronze plaques located at the front entrance to Summerall Chapel, pictured above, which listed the names of Citadel Men who died in the service of their country in time of war. My “knob” year I always felt drawn to these plaques whenever I briskly walked in the gutter past the chapel, but I never stopped to inspect them for fear of an upperclassman mistaking my interest in history for loitering. For freshmen, building entrances are places to cover and uncover and keep moving, not places to stop and reflect. Fortunately, in my third-class (sophomore) year I was finally able to sufficiently examine the plaques. I now must admit, as I described in my first post, that the names did not stick with me nor did I learn during my studies their faces or stories.

Twenty-three years hence, I have just begun to know the names, faces and stories of the Citadel Men at Margraten…2Lt Frederick Davenport Melton ’45 who shares the family name of my senior year roommate, Paul Melton ’89, and who’s father wrote to the school’s President Gen. Summerall, in response to the General’s request for a photograph, that his son was buried in Margraten, Holland, and that his grave had been adopted and tended to by a local church [1]; 2Lt Creswell Garlington, Jr. ’44 who was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for courageously leading his platoon in its assault on the Siegfried Line; 1Lt Edwin Karl Newman ’39 who was killed near Montfort not far from my home; 1Lt William Milling Royall ’42; 2Lt Arthur Bradlee Hunt, Jr. ’44; Pfc Wilson Adelbert Wendt ’45; SSgt Robert Cowan Rolph ’46; and Sgt Edward Gray Cherry, Jr. ’46. Their individual In Memoriam pages are found here.

While our eight Citadel Men are not mentioned by name in his recently published book, “The Margraten Boys”, author Peter Schrijvers explains in intriguing detail how the Dutch have adopted, watched over, and cared for all the American graves at Margraten since 1945. Mr. Schrijvers has captured the heart and soul of the adopters and the small volunteer organization which arranged enough school children and adults to place flowers on all of the more than 17,000 graves the first Memorial Day ceremony at the cemetery, May 30th, 1945. He shares stories from the American and Dutch families who have exchanged correspondence and photographs over several generations as they continue to remember the soldiers who fell in the prime of their lives. He tells the story of very special individuals who made it their personal mission to provide comfort to the families left behind in America, how the Dutch refer to those buried at Margraten as “our boys”, and how the “boys” actually include four “girls”.

While our eight Citadel Men are not mentioned by name in his recently published book, “The Margraten Boys”, author Peter Schrijvers explains in intriguing detail how the Dutch have adopted, watched over, and cared for all the American graves at Margraten since 1945. Mr. Schrijvers has captured the heart and soul of the adopters and the small volunteer organization which arranged enough school children and adults to place flowers on all of the more than 17,000 graves the first Memorial Day ceremony at the cemetery, May 30th, 1945. He shares stories from the American and Dutch families who have exchanged correspondence and photographs over several generations as they continue to remember the soldiers who fell in the prime of their lives. He tells the story of very special individuals who made it their personal mission to provide comfort to the families left behind in America, how the Dutch refer to those buried at Margraten as “our boys”, and how the “boys” actually include four “girls”.

Most every American is familiar with the cemetery at the D-Day beaches in Normandy, France where six of our Citadel Men rest in peace and one is remembered on the Tablets of the Missing, but, as Mr. Schrijvers points out, it was not until the beginning of this millennium that the French at the Normandy and Brittany American Cemeteries copied the grave adoption program of Margraten. In the book we learn how American paratroopers were moved from temporary cemeteries near Nijmegen and Eindhoven to their final resting place at Margraten and how their adopters made the journey from Brabant to Limburg to visit them. We learn how survivors of the Hunger Winter of 44-45 during which 16,000 Dutch starved to death were so thankful for the airdrops of food from American planes that they, too, were compelled to adopt a grave at Margraten. Most heart wrenching are the stories from the Limburgers who opened their homes to the G.I.s, shared meals, and befriended them following the liberation of south Limburg in September 1944 only to find their G.I.’s name painted on a white cross or Star of David later at the Margraten cemetery. In many homes in Limburg, and elsewhere, framed photos of “Margraten Boys” take a place of honor amongst family photos. Mr. Schrijvers has caught the essence of Margraten – as a cemetery it is unique because it continues to live and breathe thanks to the Dutch and their adoption program.

Related: Citadel Men, Margraten Boys, and a Debt of Honor

This past weekend the people of The Netherlands observed Remembrance Day (May 4th) and Liberation Day (May 5th). At 8 p.m. on May 4th everything fell completely still here as the country collectively held two minutes of silence in honor of its war dead, including its “Margraten Boys”. Wherever you were, whatever you were doing, you stopped, and you remembered.

In 1945, the Dutch, and most notably the villagers of Margraten, made a promise to look after the fallen liberators and in doing so provide comfort to the American mothers and families who could not visit their loved one’s grave. All 8,301 graves at Margraten have been adopted, and the adopters take their promise just as seriously today as they did in 1945. I will not be surprised to find a sea of flowers at Margraten when I visit there on Memorial Day weekend later this month. Thanks to these warm-hearted people, we should not worry about our Citadel Men here. They, like all the “Margraten Boys”, are well cared for and always remembered. I hope one day soon to meet the people who are watching over our Citadel Men so I may personally thank them and let them know that we, too, have not forgotten.

/RL

[1] “We Honor Their Memory – Origins of the Summerall Chapel War Memorial Tablets”, Steven Smith ’84, 2008

Comments (6)